Some Ecological principals for Thinking about Aquariums as Ecosystems

Thinking about your aquarium as an ecosystem requires that you consider all of the living organisms in your aquarium and how they interact with each other and the environment. No aquarium is too simple for this framework. Some of the more complex aquarium environments still have as many ecological questions as there are answers. Enrich your aquarium experience with an understanding of the ways that the organisms in your aquarium contribute to its health or disease. If you do this, you will learn how to hack the biology of your aquarium for an aquarium that’s easier to take care of and more interesting.

An Ecosystem is a biological community of interacting organisms and their physical environment. When you start a new aquarium, your job is to help these interactions form in a favorable way. When you are maintaining an aquarium, your job is the same; but, sometimes made more challenging by your tiny ecosystems increasing complexity. This series of blog posts will teach you 5 important ecological principals that apply to your aquarium. It will cover how ecosystems form, how to choose the ecosystem that is best for your aquarium, how to maintain a healthy ecosystem in your aquarium how livestock choices can affect your aquariums ecosystem, and how behavior can change as populations decrease or increase in size.

Without Further Ado, Here is part one of the series. If you enjoy the content and find it valuable please share with fellow hobbyists and people considering starting there first aquarium

Imagine an island formed in the tropical Pacific Ocean. These are borne from cataclysmic events. Molten mantle pours from the crust below until it reaches above the water’s surface and cools. The temperatures of the rock prevent life from developing for a period of time and what your left with is a totally sterile piece of habitat. How does an island like this become a complex habitat like the Hawaiian Islands or the Galapagos?

The first colonizers of islands are often grasses. Low lying plants with shallow roots that can slowly break apart the rock to start forming a soil. The animals that a habitat like this can support are usually small and with a relatively low diversity. As the rock becomes nutrient rich soil, larger plants can survive. Bushes and small trees continue to work the rock into soil and eventually shade out the grasses on some of the island. These taller growing plants outcompete the grasses for light and can support a wider variety of animals. In time, larger and larger plants can survive, increasing the three-dimensional habitat. Niches develop and are exploited by and ever-increasing diversity of wildlife. These gradual changes to an ecosystem leading to more complex ecosystems is called succession; with more complex habitats establishing over less complex habitats.

Let’s continue the analogy of succession with the Galapagos and Hawaiian Islands. Both island chains were formed by hotspots in the earth’s mantle. They are also both comfortably situated in the tropical latitudes. Yet they host a vary different assortment of wildlife and habitats. The Galapagos famously has tortoises, marine iguanas, and very dramatic racer snakes- yet Hawaii had no native reptiles. Hawaii is roughly three times the size of the Galapagos, and also significantly further away from a continental landmass. The differences in flora and fauna on the two islands are explained by three principals of island colonization. For any organism to survive on an island it has to 1. Be brought to the island, 2. Be able to survive the journey to the island, and 3. have the right environment present. For an organism to establish on an island it also needs the correct physical, chemical, and biological resources to allow it to thrive and reproduce.

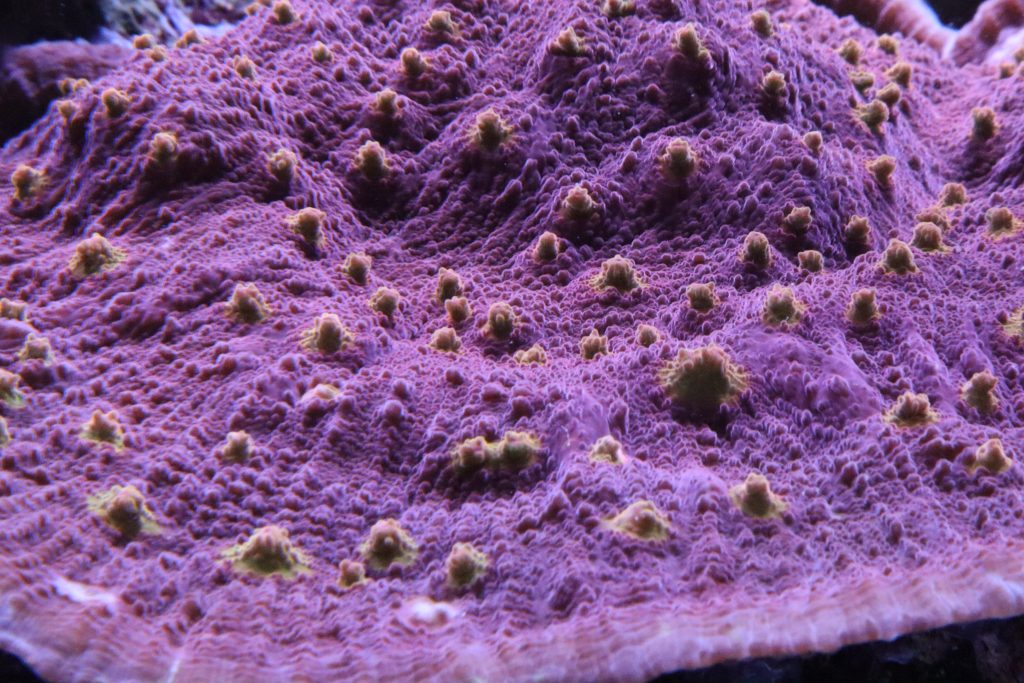

The principals of succession and island colonization apply to aquariums in many ways. Your brand-new aquarium with gravel or sand, decorations or rock and freshly mixed water is a relatively sterile environment. Some of what grows will have been transported in the water, through the air, and on the substrates, but the larger animals and plants will be added at a later time. The bacteria and microbes that populate in an aquarium will undergo a similar succession to the grasses and shrubs and forests of the hypothetical island used in the example above. The grasses can be thought of as the problematic and uglier algae and microbes that form in newer tanks and the forest the pristine mature aquarium with the right communities of microbes to prevent problem algae.

The types of animals and plants that you add and when you add them will have positive or negative effects on this process. Add fish before the biological cycle has occurred and they will likely die of ammonia and nitrite poisoning. Add plants before the biological cycle has occurred and your cycle may take longer as the plants compete with the bacteria for the available ammonia. A Sand or gravel sifting organism will disturb the biological filtration when its developing. If you put sensitive animals in too soon, they may not have the nutrients or stability to support them. Likewise, adding to many herbivores before sufficient algae has grown will result in their starvation. Carefully consider the needs of your aquarium and how the behavior of the animals you are adding will affect the development of the ecosystem.